Los Otros

The Others

Las personas somos innatamente sociales, no podemos vivir sin la presencia y la interacción de más seres humanos. La soledad absoluta es sinónimo de muerte.

De hecho, nuestra existencia empieza con el aporte genético de dos personas de sexos opuestos y, para formamos y crecer, necesitamos del maravilloso biosistema del vientre de una mujer con la que compartimos nuestros primeros meses de vida y nuestras primeras experiencias vitales.

Dentro del vientre, captamos ya los estímulos que vienen del exterior, especialmente las voces de aquellos que nos aprecian y aprendemos a apreciarlos también. Y al nacer, descubrimos en ellos a la familia de la que somos parte y con la cual desarrollamos nuestra identidad.

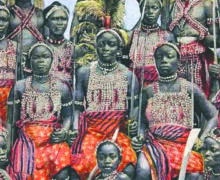

Luego viene un descubrimiento crucial: la existencia de “los otros”. Ellos no son nuestra familia y son mucho más numerosos que ella. Aprendemos a “clasificarlos” para asimilar su existencia: vecinos, cantantes, actores, políticos, vendedores, extranjeros, etc. Inclusive “extraños” (aquellos sin clasificar).

Al final, aunque intuimos que todos ellos son fundamentalmente seres humanos, caemos en el error generalizado de considerar a “los nuestros” como de mayor valor que “los otros”. Jerarquizamos, entonces, a las personas. O, peor aún, llevamos estas ideas a su consecuencia extrema: “los otros” son enemigos.

Por esto, la historia humana no es más que el relato de la lucha absurda y suicida de “los nuestros” contra “los otros”. Absurda, porque parte del falso principio que los seres humanos son diferentes en esencia, dignidad y valor. Y suicida, porque al convertir a “los otros” en enemigos, los obligamos a que ellos hagan lo mismo con nosotros.

Este principio es tan tóxico que al llenarnos de sospechas y miedos contamina aun la relación con “los nuestros” y nos enfrentarnos a ellos. Nadie gana aquí, excepto la soledad y el mortal aislamiento.

¿Es que no hay otro camino? Claro que sí. El camino de reconocer que “los otros” son semejantes a “los nuestros”, porque tienen la misma dignidad y el mismo valor, y que eso, antes que enemigos, nos hace prójimos suyos, hermanos humanos.

El camino es repetirnos diariamente que no somos seres “univivientes”, aislados o independientes de los demás. No existimos para ser ermitaños ni para vivir enfrentados. Nuestro diseño original nos grita desde el inicio que “los otros” son tan semejantes como “los nuestros” y que formamos una gran familia humana.

No acallemos esa voz y aprendamos a amar al prójimo como a nosotros mismos.

People are innately social, we cannot live without the presence and interaction of more human beings. Absolute solitude is synonymous with death.

In fact, our existence begins with the genetic contribution of two people of the opposite sex and, in order to form and grow, we need the wonderful biosystem of the womb of a woman with whom we share our first months of life and our first life experiences.

Inside the womb, we already capture the stimuli that come from the outside, especially the voices of those who appreciate us and we learn to appreciate them too. And at birth, we discover in them the family of which we are part and with which we develop our identity.

Then comes a crucial discovery: the existence of “the others.” They are not our family and they are much more numerous than her. We learn to “classify” them in order to assimilate their existence: neighbors, singers, actors, politicians, vendors, foreigners, etc. Including “strangers” (those unclassified).

In the end, although we intuit that all of them are fundamentally human beings, we fall into the generalized mistake of considering “ours” as of greater value than “the others”. We rank, then, people. Or, worse still, we take these ideas to their extreme consequence: “the others” are enemies.

For this reason, human history is nothing more than the story of the absurd and suicidal struggle of “ours” against “the others”. Absurd, because it starts from the false principle that human beings are different in essence, dignity and value. And suicidal, because by turning “the others” into enemies, we force them to do the same to us.

This principle is so toxic that by filling us with suspicions and fears it even contaminates the relationship with “ours” and we confront them. No one wins here except loneliness and deadly isolation.

Is there no other way? Of course. The path of recognizing that “the others” are similar to “ours”, because they have the same dignity and the same value, and that, before being enemies, makes us their neighbors, human brothers.

The way is to repeat to ourselves daily that we are not “univivient” beings, isolated or independent from others. We do not exist to be hermits or to live in conflict. Our original design shouts to us from the beginning that “the others” are as similar as “ours” and that we form a great human family.

Let’s not silence that voice and learn to love our neighbor as ourselves.